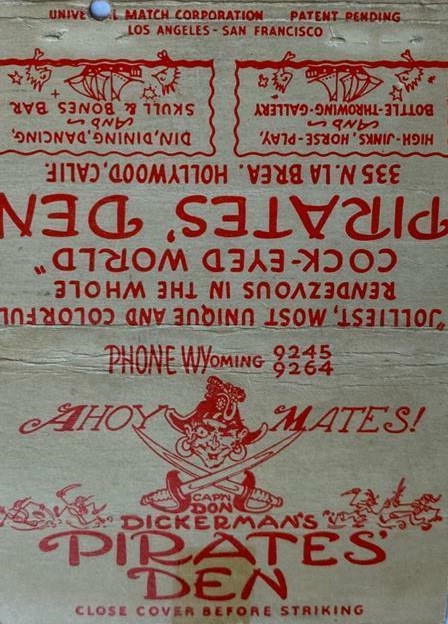

The Pirate’s Den Hollywood opened at 335 N. La Brea on May 8, 1940. Fronted by Don Dickerman, the club’s backers included Rudy Vallee, Jimmie Fidler, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Fred MacMurray, Ken Murray, and Tony Martin.

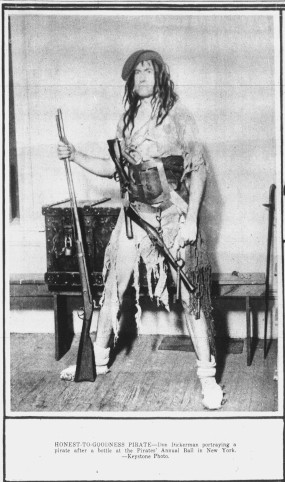

Don Dickerman was well known at the time for his Greenwich Village club The Pirate’s Den, which, like its later Hollywood successor, was decorated in the pirate theme with servers in pirate garb. The original Pirate’s Den opened in 1916 and burned down in November 1919; it would be rebuilt by 1921. (Douglas Fairbanks’ 1921 film “The Nut” also recreated the interior of The Pirate’s Den on the studio lot).

Dickerman created other themed clubs, such as the Heigh-Ho, where Rudy Vallee (whose catchphrase was “Heigh-ho everybody”) rose to national fame. Vallee bought a property on Kezer Lake in Maine, near Dickerman, and called the boathouse “The Pirate’s Den.”

Dickerman declared bankruptcy in August 1932, telling the court he only had “five old suits of clothes” to his name. He left New York and headed to Miami, where in January 1934 he advertised for backers in a new venture. He decorated the Serenade restaurant, which opened in February 1934.

By late 1934, Dickerman had the resources he needed for a new Pirate’s Den, located at 2300 NW 14th Street. The mayor of Miami, Louis F. Snedigar, attended the grand opening on December 29, 1934. “As a kid I liked to play pirate,” Dickerman told reporters. “I am still playing.”

Advertising for decor. The Miami Pirate’s Den would feature pirates (duh), chains, anchors, nets, boats, double-barreled pistols, cutlasses and a ship’s brig. The Miami Tribune,12/23/1934

The Miami Pirate’s Den was only open seasonally. As of December 1938, Don was getting ready to open a second Pirate’s Den in Washington, DC. Although Don told his Miami fans that he intended to return to his “southern home” the following season as usual, the Miami Pirate’s Den did not reopen. Located at 3135 K St. NW, the DC Pirate’s Den opened in January 1939. Despite three decks of fun– the Main Deck, a Gun Deck, and a musical Poop Deck (for the orchestra)–it didn’t last. In December 1939, the club was closed by court order for non-payment of rent. Its equipment and fixtures would be sold to pay the back rent on February 19, 1940. By then, Don was in Hollywood.

AHOY HOLLYWOOD

Whitney Bolton of the Philadelphia Inquirer reported in her “Hollywood Snoopshots” column of February 11, 1940, that Don Dickerman would play a pirate in Errol Flynn’s picture “The Sea Hawk,” after which he and Flynn would go into partnership at the Isthmus on Catalina Island in a West Coast Pirate’s Den. Isthmus was the South Seas-themed film set turned actual bar, from the 1935 filming of “Mutiny on the Bounty,” which had sparked a Hawaiian/South Seas themed bar craze in Hollywood. (See my previous post, here).

On February 12, 1940, Hedda Hopper reported that Dickerman was staying with Flynn at Flynn’s home while appearing in a bit part in “The Sea Hawk.”

Hugh Hough of the Miami Herald reported on March 9, 1940 that Dickerman had driven out to Hollywood determined to open a Pirate’s Den there. Peter Pell of the Miami News also noted on March 18, 1940 that Dickerman was opening a Pirate’s Den type club with Flynn. James McLean of the Miami News added on March 30, 1940 that Rudy Vallee and Jimmie Fidler would be partners in the venture.

In August 1940, Radio and Television Mirror magazine wrote: “The real reason Rudy Vallee is promoting that new Pirate’s Den Night Club in Hollywood is to pay a debt of gratitude to Don Dickerman, who will manage it. As owner of the famous Heigh Ho Club in New York, Dickerman gave Vallee his start ten years ago. It was there Rudy climbed to fame as a band leader and crooner. It was at the Heigh Ho Club that Rudy originated the famous salutation “Heigh-ho everybody.” So you can see that it’s true that Rudy never forgets a friend. Dickerman had been playing extra parts in motion pictures, when Rudy accidentally ran into him at a night club. Rudy personally solicited such stars as Bing Crosby, Fred MacMurray, Errol Flynn, Bob Hope, Johnny Weismuller and others to lend their financial support by going into the club as partners with him. The kitty holds a nifty $75,000 to make certain it will be a success.”

The new Hollywood Pirate’s Den opened on May 24, 1940.

Rudy Vallee, Bob Hope, Ken Murray, Tony Martin and Jimmie Fidler at the Hollywood Pirate’s Den. Radio & Television Mirror, August 1940.

The new Hollywood Pirate’s Den was located at 335 N. La Brea near the corner of Beverly. I previously posted my research on this building on the website “Noirish Los Angeles.” A person took my research and comments and posted it verbatim on his own website, without crediting the source. Readers of that site no doubt have the impression that it is his own research. I’ve since updated the information and am including it all below.

335 N. La Brea was built in 1927 as Eads Castle, operated by Ephraim Cook Jr. and Sara G. Eads formerly of Kansas City. “An attractive structure of Spanish type architecture” built at a cost, including furniture, of $100,000. “A radical departure from the orthodox type of café housing.” It was a family café, also popular with the after-theater crowd.

An earlier celebrity connection for 335 N. La Brea: in late 1929 the café was sold to Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Al Gilmore and Lou Anger for $25,000 and renamed Roscoe’s.

Arbuckle had the café for less than six months. In February 1930 a complicated but successful lawsuit kept the sale to Arbuckle et al from becoming finalized. May 22-24, 1930 the Eads celebrated its grand re-opening as Eads Castle.

Just so we’re clear… Fatty Arbuckle is NOT associate with this café anymore. June 1930 Eads Castle ad

By late May 1932, it was operating as Casa Brea Dinners. Don’t get too attached to that name…

On October 31, 1933, 335 N. La Brea reopened as the 3 Little Pigs cafe, named for the Disney cartoon released that year, owned by Mark M. Hansen of the Marcal Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. He was arrested in November 1933 for violation of the state liquor sales tax law and charged with failure to take out a liquor license. In June 1934, Hansen was in court again because the 3 Little Pigs was selling liquor within 1.5 miles of the Soldier’s Home and had failed to report it. (Now that liquor sales were legal, it was taxed and regulated by the State Board of Equalization and subject to local law and violations were frequent). Hansen promised the board that he intended to operate his establishment in a legal manner. The club added a cocktail bar and banquet hall in October 1935. 335 N. La Brea continued as 3 Little Pigs into May 1936.

On September 1, 1936 it had a grand re-opening as El Mirador Cafe.

In February 1937, El Mirador proprietor Benjamin J. Zimmer, manager H.R. Newman, and bartender Robert Rubin were arrested by Hollywood police for running a check/banking scheme. Exit El Mirador.

On October 8, 1937, 335 N. La Brea opened as the Waikiki, one of many new Hawaiian-themed clubs about town. Johnny Hall and Bob Cabaniss, operators. I covered it on my post on the Hawaiian Craze, here.

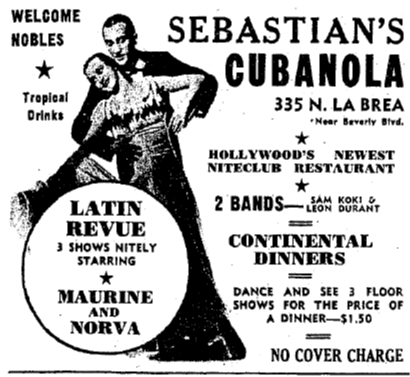

By June 1938, 335 N. La Brea had gone Latin (still featuring tropical drinks) as “Sebastian’s Cubanola” with Maurine and Norva, Sam Koki and Leon Durant.

The Sea Hawk, starring Errol Flynn, had a preview at the Hollywood Warner’s Theater on July 17, 1940. The film began its first run at Warners’ Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles theaters on August 24, 1940. The Sea Hawk was so popular with audience that it was held over for a second, then a third, week. It has its last showing at Warners’ flagship theaters on September 11 before moving to other houses. If Dickerman appears in the final cut of the film, he is not credited.

Battle scene footage from the 1924 silent film Sea Hawk filmed off Catalina were spliced into the 1940 film (same title, different plot). LA Times 8/3/1924.

Preview for The Sea Hawk (“The Robin Hood of the Seas”) held July 17, 1940 at the Hollywood Warner Brothers Theater.

The Hollywood Pirate’s Den got tons of free publicity thanks to its celeb owners and patrons. Dickerman’s association with the venue lasted only a few months, however. By October 1940, he had called it quits. On January 10, 1941, Miami Herald columnist Dorothy Day reported that Don was was back in Miami and planning to open a new Pirate’s Den. “Too many cooks” was later the stated reason for his Hollywood departure.

Joe Bart (formerly of La Conga) became manager of the Hollywood Pirate’s Den. The venue got some unwanted press attention in July 1941, when a Superior Court Judge complained that the establishment had charged him $6 for 3 beers and bounced him when he tried to use the telephone. As the case made national headlines, another patron came forward with a similar complaint. The Police Commission pondered the fate of the Pirate’s Den’s show license.

The club’s defenders asserted that a $2.00 minimum was quite usual for swank nightclubs and rube patrons were getting confused by the “No Cover” policy. Joe Bart agreed to remove the “No Cover” signage and the license was indeed renewed later that month- as if it was ever really in doubt.

There was more negative publicity the following month. A marine, Private Ralph Kolberg, was at the club on August 11, 1941, throwing dice in the bathroom. He and a group of people (including Lou Wertheimer, formerly of Detroit’s Purple Gang; his brother Al Wertheimer had been an investor in the Clover Club) left the Pirate’s Den and went to another club, Rhum Boogie (operated by Mickey Cohen), then went on to a private party at the home of agent Phil Berg, where a brawl ensued between Kolberg and Guy Rennie, a singer/comedian from the Pirate’s Den floor show. Treated at the San Diego Naval Hospital for a skull fracture and several broken ribs, Kolberg said he “woke up in a pool of blood and heard a couple of guys talking about dumping [his] body somewhere.” Rennie admitted punching the marine but claimed Kolberg started it. No charges were brought. Captain W.W. White of the Beverly Hills Police Department pronounced the case closed on August 19.

This San Fernando Valley Times as for The Pirate’s Den still refers to some of the celeb owners of the club. 9/5/1941

The Pirate’s Den would continue in business for several more years to come, though between the negative publicity and the US entry into World War II, its celeb backers were seldom referenced anymore.* In October 1943, the LA Daily News referred to Vallee et al as “former owners” and asserted that Joe Bart was the sole owner. Florabel Muir, in her syndicated column that appeared in the Hollywood Citizen News on April 6, 1945, said that bickering among the former owners caused them to start avoiding the place. Muir further noted that of the original group only Fred MacMurray still had an investment in the Pirate’s Den.

The Pirate’s Den lifted the $2.00 minimum (“Just pay for what you order”) but never quite shook its reputation as a ripoff joint. San Fernando Valley Times 2/17/1942.

A wartime postcard view of the Pirate’s Den under Joe Bart. The targets in the Bottle Gallery are Hitler, Tojo and Mussolini.

A soldier added his own review in a 1943 guidebook “Sinning in Hollywood” entry for the Pirate’s Den. The 1941 incident over $6 beers cast a long shadow. Author’s collection.

On November 2, 1943, Joe Bart provided food and entertainment for an evening at the Hollywood USO. Hollywood Citizen News.

Capitalizing on a recent nostalga-driven fad for Victorian-style melodrama theaters where audiences could boo and hiss at mustache-twirling villains while scarfing free pretzels and swilling beer, on April 5, 1945, the club became a venue for a Gay 90s-style review, “Adrift in New York, “and temporarily changed its name to the “Pirate’s Den Music Hall.” Adrift in New York closed after a successful almost 2-month run and on May 31, a “gorgeous girl review” opened, “Carefree Carnival” and the Pirate’s Den soon dropped the “Music Hall.”

The Pirate’s Den remained the “Pirate’s Den Music Hall” for “Carefree Carnival” at first but soon dropped the “music hall” tag. 6/1/1945.

The Pirate’s Den provided entertainment for the famed Hollywood Canteen on June 25, 1945. Hollywood Citizen News.

The Pirate’s Den “Carefree Carnival” cast performed again at the Hollywood Canteen on August 13, 1945. It was the end- the end of WWII and the end of the Pirate’s Den. Hollywood Citizen News.

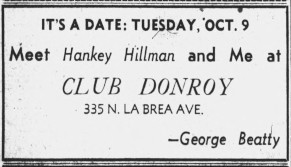

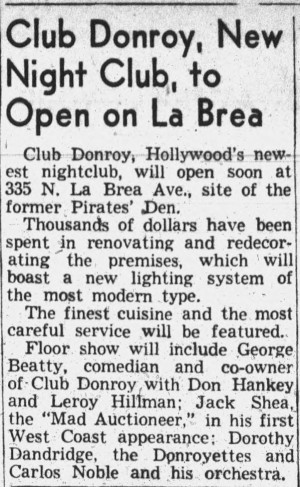

On August 21, 1945 the Hollywood Citizen-News reported that Don Hankey and Leroy Hillman of Donroy Aircraft Parts, and comedian George Beatty had purchased the old Pirate’s Den from Joe Bart and were revamping it. Their Club Donroy opened on October 9, 1945.

In March 1946, 335 N. La Brea was advertised as the new home of Charlie Foy’s club. The Foy/Donroy partnership collapsed at the last minute, however, and the club continued as the Donroy.

In April 1947, the club was referred to as “Club Stanley,” (a reference to Stanley Page, Farmer Page’s former jockey brother?). It was raided by the LAPD vice squad on April 17 for selling liquor after curfew. On July 5, it reopened as The Track.

On October 14, 1947, 335 La Brea again became a venue for a Gay 90s themed theater as the new home of Frank Fortier’s melodrama “Gaslights.”

In January 1951, the Motion Picture Relief Fund purchased the 8000 square foot building for use as its executive offices.

DON DICKSON Post-HOLLYWOOD PIRATE’S DEN

Don Dickerson may have left the Pirate’s Den but he was not done with Hollywood or California. In 1943 he became a partner in the Wooden Shoe at 7290 Sunset Boulevard.

The Wooden Shoe had been built in 1939 for Harry Zody, as a replica of the old Rembrandt House in Amsterdam. Dickerman added a “merry mermaid” cocktail bar and a buccaneer quarterdeck. He sued his partners Harry K. Curtis and Wendela Drury, on January 25, 1944, asserting that the venue had been sold on January 10 and he had not received his third of the sale price. The Wooden Shoe became Moon Mullins’ Cafe in December 1945, then the Club Tabu as of November 1946.

On September 19, 1946, Dickerman opened the Castaway Club at Newport Beach, built in the shell of the old Irvine golf club clubhouse. In 1949, his investor, Huntington Hartford, sued Dickerman for non-payment of a loan. The Castaways burned down in the wee hours of November 16-17, 1956. It was then owned by Broadway entertainer Frank H. Coburn. Dickerman died in 1981.

Don Dickerman c. 1946 at The Castaway Club, Newport. UC Irvine Library photo, Gerhardt Photograph Collection.

*

Ken Murray would open his own review, Blackouts, at the El Capitan Theater on Vine Street, in June 1942.

Rudy Vallee joined the Coast Guard in August 1942, serving as bandmaster at the Los Angeles post’s Long Beach base.

Errol Flynn became a US citizen in August 1942. He tried to join the service but was turned down due to health issues. That Fall, two young women ages 16 and 17 separately accused Flynn of statutory rape. The cases went to court in January and February 1943. Flynn was acquitted.

Tony Martin was accused and cleared of draft dodging in late 1941 and joined the Navy on January 2, 1942. Dismissed by the end of the year following a bribery scandal, Martin was subsequently drafted into the Army and assigned to the Army Air Force.

Fred MacMurray tried to join the service and was likewise turned down die to health issues. He was an active member of the Hollywood Victory Committee and civilian defense efforts.

Johnny Weissmuller, former Olympic swimming champion and Tarzan of the movies, also had health issues that rendered him unable to serve.

Bing Crosby entertained the troops in camps and on Red Cross trips overseas in addition to making recordings for service use.

Bob Hope toured extensively with his own show here and overseas, performing for the troops as well as making radio shows and recordings for service use.