Los Angeles has long has a fondness for Hawaiian music and style and Hollywood films did much to romanticize the islands as a tropical paradise prior to World War II.

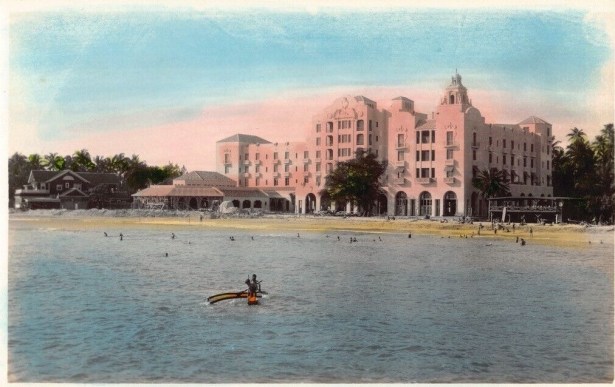

Pan-American’s Martin M-130, “China Clipper” conjured up images of romantic eastern ports and swaying palms under balmy tropical skies, which the airline capitalized on in its advertising. On April 28 1937 the China Clipper made history by completing the first transpacific flight by a commercial passenger airliner, landing at Hong Kong after having departed San Francisco on April 21st carrying 7 ticketed passengers. Honolulu was it first stop.

Honolulu native Sol Hoopii, virtuoso of the lap steel guitar, made Los Angeles his adopted home and was performing live with his trio at local venues and radio station KHJ by 1924. In 1938, he joined Aimee Semple McPherson’s ministry and devoted his career to writing and performing songs for her tours.

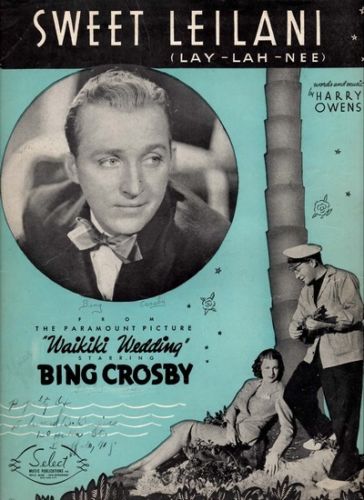

Owens met Bing Crosby when both were performing at the Lafayette in 1926. Two of the songs crooned by Crosby in the 1937 film Waikiki Wedding, “Blue Hawaii” and “Sweet Leilani,” became standards. The latter won an Academy Award for best song that year and became Bing’s first gold record. Harry Owens, who wrote “Sweet Leilani” for his young daughter in 1934, would perform the song with his band in the 1938 film Coconut Grove.

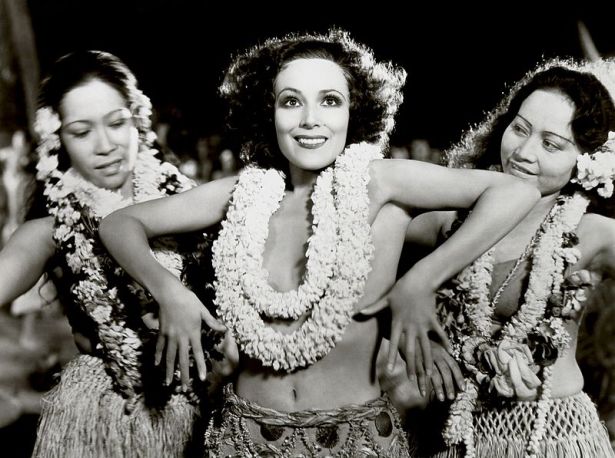

Hollywood loved a Hawaiian/Pacific Island settings; if nothing else it was a way to get the leading lady into a grass skirt. With the talkie era, they could also capitalize on the popularity of Hawaiian music and dance.

Joan Crawford in Rain (1932) based on the Somerset Maugham short story “Sadie Thompson” and set in the South Seas.

The 1935 production of Mutiny on the Bounty, based on the 1932 novel by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, itself based on real events, sparked a flurry of South Pacific themed films, peaking in 1937.

The 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty was largely filmed in California. A real life South Seas cafe opened on Catalina Island, the Isthumus.

Lotus Long in MGM’s Last of the Pagens (1936). Based on Herman Melville’s 1846 novel, Typee, it was filmed on location in Tahiti. LAPL photo.

Monogram’s Paradise Isle had some location shooting in American Samoa. Movita, who also appeared in Mutiny on the Bounty, was actually of Mexican heritage.

The aforementioned Waikiki Wedding was filmed at Paramount’s Hollywood studio, with on-location shots made in Hawaii added post-production. bingcrosby.com photo.

The Hurricane was peak prewar Hawaiian film mania. Directed by John Ford, it featured Dorothy Lamour in a sarong and a mostly shirtless John Hall. The film debuted at the Carthay Circle Theater on November 5, 1937.

Filmed in late 1937 and released in 1938, Hawaii Calls borrows the name of the popular radio show and features songs by Harry Owens. The plot, of a boy stowing away on a Hawaii-bound ocean liner, seems at least partly influenced by Sol Hoopii’s life story.

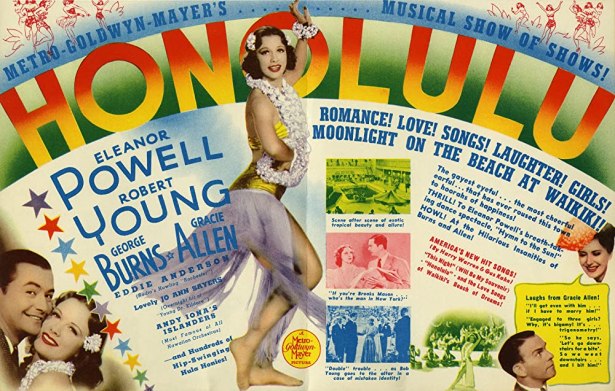

Honolulu (1939) with Eleanor Powell and Robert Young, was filmed at MGM’s studio with stock footage of prewar Waikiki Beach.

Those who craved even more escapist tropical fun could drink a rum cocktail out of a coconut in a room full of bamboo and fake palm trees. Georgia Stiffer noted in “Hawaiians at Hollywood,” published in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin on September 25, 1937, that due to the popularity of Hawaiian music and dancing in Hollywood in the 1930s “any cafe with Hawaiian atmosphere or Hawaiian music and dancers will lure the crowds. Consequently the last three years have seen the opening of many nightspots carrying the South Seas motif…”

The Cocoanut Grove

Hollywood had long known the charms of swaying palms under the stars- though the palm-filled Cocoanut Grove nightclub, located in the Ambassador Hotel, was thinking more sheik-desert-sand-palms than Hawaiian palms when it opened in 1922. The palms are supposed to have been left over from the film sets for Rudolph Valentino’s The Sheik. Well, maybe. I have a separate post on the Ambassador and the Cocoanut Grove here.

Though sheik-mania was soon passé, the Grove’s swaying palms held their lure for decades to come.

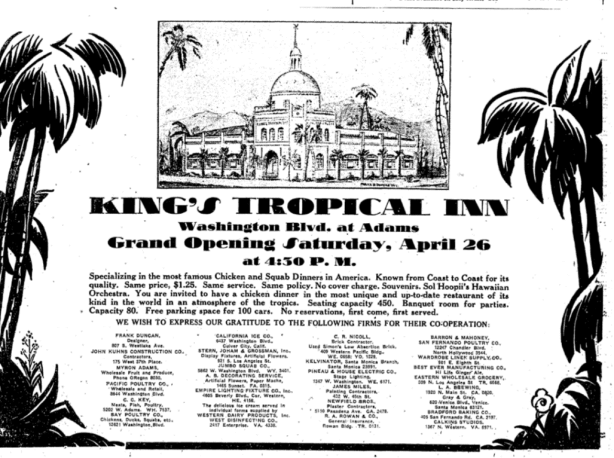

Kings Tropical Inn

Located on Washington Boulevard near West Adams in Culver City, Kings Tropical Inn was opened by John G. King in late 1925. The specialty of the house may have been southern-style chicken but the lush landscaping and interior decor were worthy of the name.

The restaurant burned down on February 17, 1930 and was rebuilt at the same site two months later in a Spanish/Moorish style with even more tropical foliage.

The first King’s Tropical Inn building c. 1927. Note the address: 5741 W. Washington Boulevard. Building along W. Washington Boulevard were re-addressed over time.

Architect Frank Dunkan designed a new Spanish/Moorish style Tropical Inn on the same site as the first one, with even lusher tropical gardens. LA Times 4/13/1930.

Sol Hoopii and his trio performed at the opening of the rebuilt Kings Tropical Inn on April 26, 1930.

Don the Beachcomber

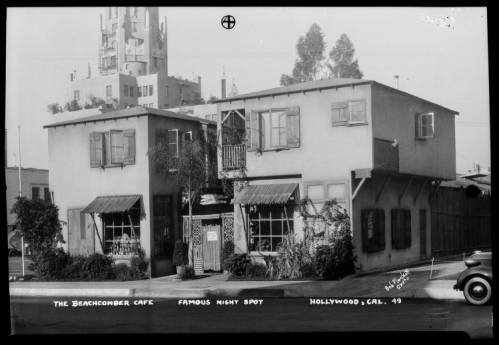

The original Don’s Beachcomber bar, founded by Ernest Raymond Gantt, opened at 1722 N. McCadden Place, on the ground floor of a small hotel, the McCadden Hotel (address: 1720 N. McCadden), not long after Prohibition ended. In the 1920s it had been The Green Hat millinery shop.

Beer and wine sales were legalized in March 1933; liquor and spirits were allowed after full Repeal in December 1933 (see my post “The Return of Beer.”). The period right after federal Prohibition ended through 1934, however, was confusing, with State liquor laws up in the air as regulations were sorted out. Don’s Beachcomber Cafe may have been operating as a “bottle club,” establishments that skirted the law by acting as a private club- they technically didn’t sell alcohol but could be served liquor from their own stash.

Captain Charles Hoy of the LAPD’s Hollywood Division vice squad raided Don’t place on September 1, 1934, for violation of State liquor regulations. Gantt would plead not guilty to the charges a few days later. (More on Hoy below in the entry on the 7 Seas).

Don appears to have tried to lease the cafe space in January 1935.

Ad leasing the hotel cafe at 1922 N. McCadden. It appears to be a misspelling of Don’s last name. 1/15/1935. Hollywood Citizen-News.

Around the same time, Gantt’s future wife, Cora Irene Sund, initiated a breach of promise (aka “heart balm”) lawsuit in Los Angeles against Michael Paul, a wealthy man who she asserted had reneged on a proposal of marriage. Paul in turn charged that Sund had “entertained a man” in her apartment while wearing a negligee. Was it Don? In any case, Sund lost her suit on April 19, 1935; she and Gantt would become partners in (briefly) marriage and (more successfully) in business. In November 1935, Sund applied for a permit to make alterations to 1722 N. McCadden Place.

The club temporarily lost its liquor license in January 1936, branded by the State Board of Equalization as an “undesirable liquor establishment” for violation of liquor ordinances.

In May 1937, Don the Beachcomber opened in a new spot across the street from the old one, at 1727 N. McCadden. Once a second location of the popular Tick Tock Tearoom at 1716 N. Cahuenga, the new location also had an expanded restaurant that served exotic Cantonese fare.

The Tropics

Harry M. “Sugie” Sugarman opened The Tropics on November 28, 1935. The Tropics’ bamboo décor and “rain on the roof” effects were said to have been inspired by the 1932 Joan Crawford film Rain.

Located at 421 N. Rodeo Drive not far from other celebrity handouts like the Beverly Hills Brown Derby, “tailor-to-the-stars” Eddie Schmidt and the Beverly-Wilshire Hotel, it was billed as “the informal cocktail lounge and dining room of the motion picture industry” and did attract a rare mix of both movie star and Society clientele.

“So, really- are you two married or not?” Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard yucking it up with Anita Loos John Emerson at The Tropics, 1936. LAPL photo.

Sugie’s original Tropics in Bev Hills remained as popular as ever throughout the 1940s. In 1953 new owner Bob Crane (the ex- Mr. Lana Turner) renamed it The Luau and kept the tropical atmosphere until the building was demolished in 1979.

The 7 Seas

Located at 6904 Hollywood Boulevard across the street from the Chinese Theater, the 7 Seas featured rain on the roof effects and a hula dancer floor show. It was originally run by Ray Haller. Haller applied for a permit to make alterations to the building, formerly used as a store/office space, on November 7, 1935 and it was serving up the tropical atmosphere starting c. December 1935/January 1936. Georgia Stiffler’s “Hawaiians at Hollywood” piece for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin on September 25, 1937 credits Haller with originating the tropical storm behind the bar effect, later much copied. She also notes that Haller’s decor was more Tahitian than Hawaiian and included “an abundance of velvet paintings of undraped Polynesian maidens, painted with some vivid and mysterious Tahitian dye that makes them very beautiful and fascinating.”

Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard must have been fans of LA’s tropical cocktail spots. Photographed at Sugie’s Tropics (see above), in January 1936, gossip columnist Read Kendall reported that they had been spotted at the 7 Seas. 1/29/1936. LA Times.

In May 1937, the 7 Seas was raided by the LAPD Hollywood vice squad, led by Charles Hoy (who had raided Don the Beachcomber in 1934), and cited for violating the liquor closing laws. The Shaw administration and LAPD’s connection to protected vice was under fire at the time, the result of citizen committees for reform, led by Clifford Clinton and others.That Hoy, now promoted to the rank of Detective Lt., raided the 7 Seas means they were either making a big show of enforcing the liquor laws or Haller hadn’t greased Hoy’s palm sufficiently.

The “World Famous” 7 Seas featured floor shows and dancing to the house band, led by Eddie Bush and his Hawaiians. 1/27/1939. LA Times.

Bob Brooks had taken over the Seven Seas by January 1942. Though Brooks is generally said to have added the velvet paintings, as noted above, Haller had them before Brooks. Brooks may have added to the collection. An admirer of artist Edgar Leeteg, he reportedly visited Leeteg in Tahiti to personally select the paintings.

In 1942, Brooks also operated the new Nevada Biltmore in Las Vegas at 614 N. Main Street, with the tropical-themed 7 Seas Room, which like its Hollywood counterpart featured Leeteg paintings.

The Bamboo Room of the Hollywood Brown Derby

The Bamboo Room cocktail lounge debuted to the public on February 7, 1936, located at 1628 N. Vine Street inside the Hollywood Brown Derby (second of the chain’s restaurants, which had opened in 1929). Carole Lombard hosted a private party at the venue on February 5, a few nights before it opened to the public. A press preview was held on February 6. Gossip columnist Jimmy Fidler called the new space “the most ultra of the Hollywood cocktail bars.” Replete with bamboo (duh) and zebra-print upholstery, it had its own entrance just south of the main one, with access to the dining room. In April 1940, the bar added a television set! The Bamboo Room was remodeled as the Record Room in 1954.

Hawaiian Paradise

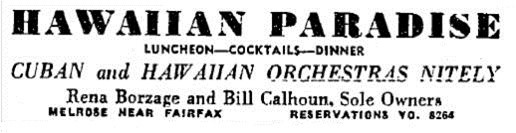

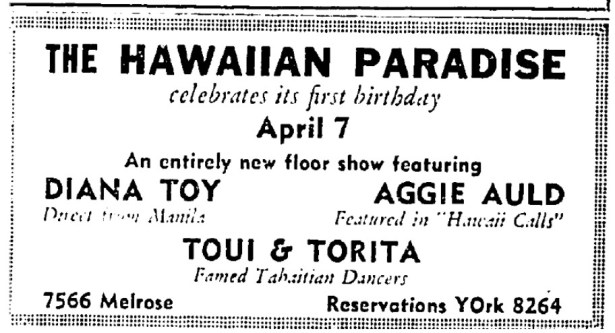

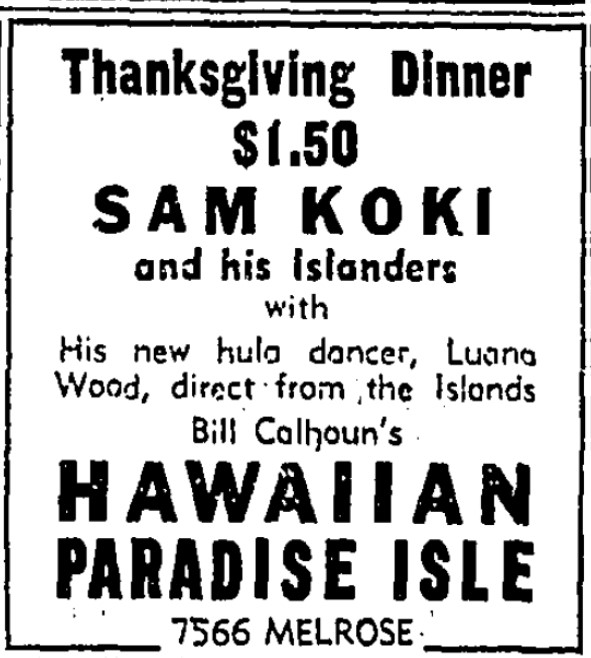

Hawaiian Paradise opened at 7566 Melrose Avenue on April 7, 1937. The owners were Bill Calhaun, George Mason and Lorena “Rena” Rogers. Rogers was an ex-actress and, from 1916 to 1941, wife of actor-turned-director Frank Borzage. After giving up acting, Rena took many trips to Hawaii, and back in Hollywood would throw huge Polynesian-themed parties with signers and hula dancers to entertain.

Hostess and club owner Rena Rogers, wearing a tropical lei, with husband Frank, right, directors Ernest Lubitch (far left) and William Wellman (in the polka-dot tie) and actor Richard Dix.

Hawaiian Paradise celebrated its 1-year anniversary on April 7, 1938. Later that year, Mason was out; Rena and Bill Calhoun remained owners. By 1939 Calhoun alone was the face of Hawaiian Paradise, now known as “Hawaiian Paradise Isle.” In February 1940, it became the Hawaiian Paradise Ballroom, a last gasp of the tropical theme.

Later that year, 7566 Melrose became the latest outlet of “Club 41” fronted by George Distel, and was closed by the courts for multiple violations of State liquor laws. In 1947 the building was remodeled as the Horton Dance Theater.

Recognizing the competing popularity of Latin music in the latter part of the 1930s, the club alternated Cuban and Hawaiian rhythms on different nights. Rena Borzage and Bill Calhoun were now sole owners. 8/18/1938. LA Times.

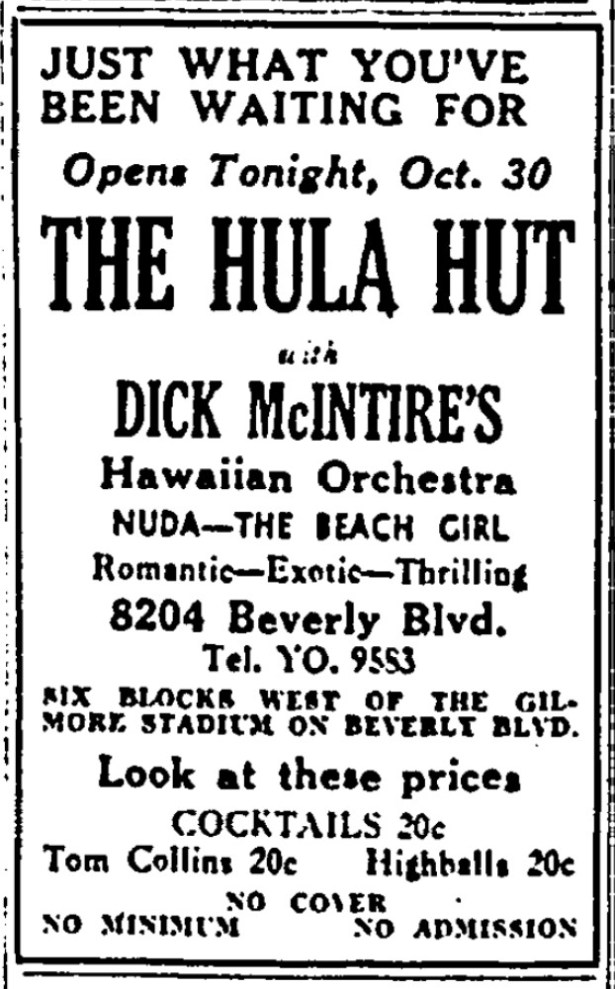

The Hula Hut

Built as a dining pavilion in 1927, in 1932 8204 Beverly Boulevard had housed the Ye Bull Pen restaurant after it moved from downtown Los Angeles.

In January 1936, it was operating as the Frolic Inn, and was cited by the State Board of Equalization (which regulated State liquor laws after Prohibition) as an “undesirable liquor establishment” along with the Clover Club and Don the Beachcomber.

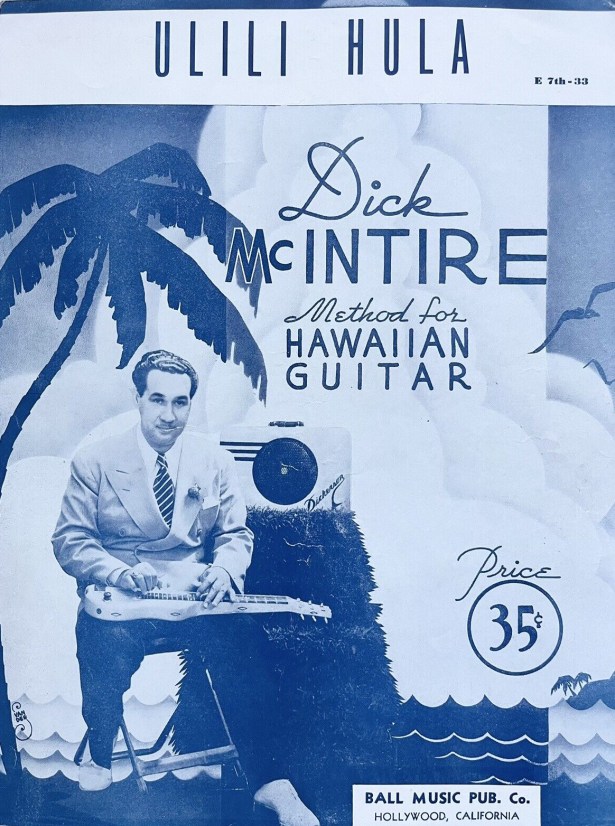

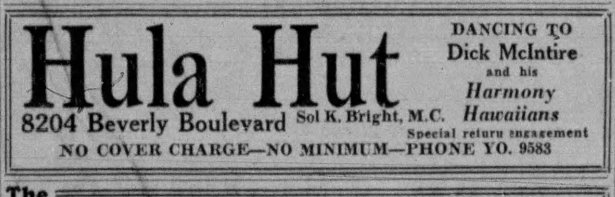

The Hula Hut, operated by Art Roy, opened on October 30, 1936, with “Nuda the Beach Girl” and Dick McIntire. It had no Polynesian style decor- just the name, Hawaiian music, and hula dancing.

Hula Hut opening night ad 10/30/1936.

Hula Hut opening night ad 10/30/1936.

Hawaiian-born steel guitarist Dick McIntire, a Navy veteran, moved to Southern California after World War I. He performed in many Hawaiian-themed films made in the 1930s. He died in 1951.

The Hula Hut exterior c. December 1937 when Andy Iona and Sam Koni were appearing. The neon roof sign appears to be a redesign of the Ye Bull Pen’s sign, which had moved with the restaurant from a previous location at 633 S Hope St. LAPL photo.

Ken Young took over the Hula Hut circa 1940. As “Ken’s Hula Hut,” it lasted for about two years. The building was demolished in December 1965.

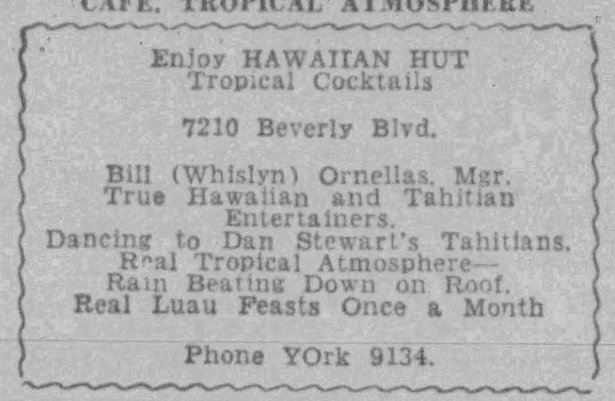

The Hawaiian Hut

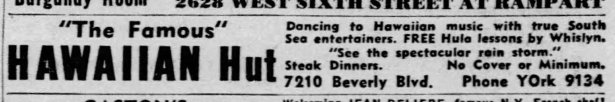

The Hawaiian Hut opened down the street from the Hula Hut at 7210 Beverly Boulevard in late 1936/early 1937, originally operated by Tony Guerrero with Bill Ornellas, whose nickname was “Whistling/Whislyn/Whislin’.” Built in 1928, the building had previously housed a series of short-lived cafes and clubs before the Hawaiian Hut came along.

Hawaiian-born Tony appeared in a few films and was married to former child actor Charlotte “Peaches” Jackson. He sold his interest in the Hawaiian Hut by 1940 and the couple moved to Honolulu where they operated a restaurant, The Tropics at Waikiki.

Ornellas’ Hawaiian Hut featured not just mere rain on the roof but an entire tropical storm effect. On July 13, 1942, the hut was damaged by an arson-set fire; it reopened September 2, 1942 and continued here through 1945.

Ad for the Hawaiian Hut promoting its rain storm on the roof effect and Dan Stewart’s Tahitian Entertainers, tropical atmosphere, tropical cocktails, and a monthly luau feast. 6/9/1942. LA Times.

Whisling Ornellas would go on to run another Hawaiian-themed club, Whisling’s Hawaii, at 6507 Sunset Boulevard, a building constructed in 1922 for the Holly-Sunset Market. It operated through 1956, often hosting jazz acts.

Gene’s Hawaiian Village

Located at 10637 S. Vermont Avenue, Gene’s Hawaiian Village opened as a dance pavilion about 1932. Run by Harry Eugene Long, the venue notably featured native performers. Both Dick McIntire and Sal Hopi performed here with extended engagements.

The “village,” located to the north of the cafe itself, consisted of Samoan huts, canoes, beachcomber shacks, and “everything authentic enough to transport you in imagination to another world,” according to columnist Win Morrow. Gene’s operated into 1948.

Ad for Gene’s Hawaiian Village featuring dancing to Dick McIntire and his Harmony Hawaiians, 5/14/1936. LA Daily News

Ad for Gene’s Hawaiian Village with Sol Hoopii, not to mention “Mexican Pete” 8/17/1936. LA Daily News.

Gene’s Hawaiian Village. Photo from mytikilife.com (https://mytiki.life/tiki-bars/genes-hawaiian-village#&gid=1&pid=1)

Waikiki

This short-lived Hawaiian-themed club opened on October 8, 1937 at 335 N. La Brea near Beverly Boulevard. The building was constructed in 1927 as Ead’s Castle restaurant.

Billed as “Honolulu transplanted to Hollywood,” the opening of Waikiki featured the Noe-Noe room cocktail lounge, Hawaiian songbird Lena Machado, and a floorshow featuring Prince Lei Laini and Sol Hooppi’s Hawaiian orchestra. Blink and you missed it- the club folded before the year was out, owners Johnny Hall and Bob Cabaniss citing “financial difficulties.”

The venue went on to become the nautical/piraate themed Don Dickerman’s Pirate’s Den, which has its own post, here.

Zamboanga

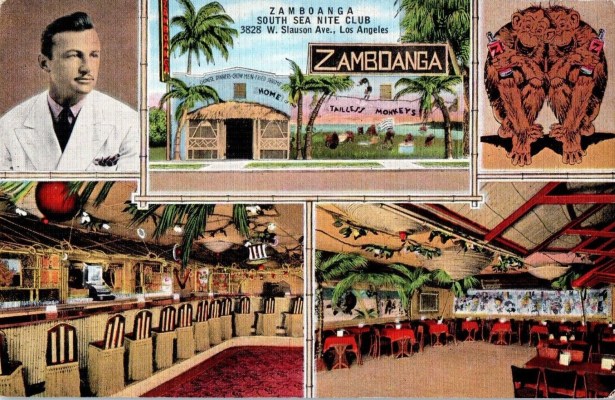

The Zamboanga South Seas nightclub, “Home of the Tailless Monkeys” was the creation of Minnesota transplant Joe Chastek. Chastek discovered the South Seas as a young man; he was living in Honolulu as of 1930 per US Census records, and in Manilla in 1935.

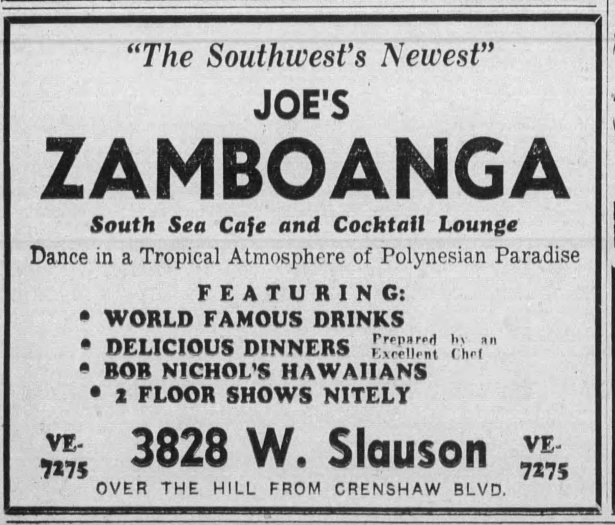

Originally called “Joe’s Zamboanga” South Sea Cafe and Cocktail Lounge, the venue opened at 3828 Slauson Avenue in late 1938 and featured performers such as Bob Nichols as well as an annual luau. By early 1940 it was just “Zamboanga” and the “tailess monkeys” had made their appearance. In June 1941, Chastek expanded the cafe and added a 17 foot neon-lit monkey sign to the roof.

Ad for Joe’s Zamboanga. “Dance in an atmosphere of Polynesian paradise.” 10/7/1938. The Southwest Wave.

Slauson Avenue in April 1940, photographed by Dick Whittington. The Zamboaga is seen in the middle right, before its 1941 expansion. USC photo.

Celebrate the 4th with Joe Chastek (and the Tailless Monkeys). Specializing in Tropical Drinks and Chinese Food. Yes, Please. LA Daily News 7/3/1942.

During the war, in December 1944, “Trader Joe” Chastek opened a second club, the Trade Winds, at 334 S. Market Street in Inglewood, again with a monkey theme.

After the war, in late 1947, Chastek would open a third South Seas-themed club, the Vagabond House, at 2505 Wilshire Boulevard, in the Masque Theater building.

Coral Isle

Niel [sic] Murphy opened the Coral Isle at 9349 Washington Boulevard, across from the RKO/Selznick International studios in Culver City on April 12, 1939. It featured murals by Frank Bowers, decorative matting and bamboo everything. The house specialty was chicken dinners.

Harold La Van took over Coral Isle in July 1941. La Van had operated a previous cafe in Venice, the Bambu Hut (discussed below) as well as the Rhumba Cabana in Santa Monica. La Van expanded the Coral Isle in 1944. It was soon taken over by brothers Phil and Lou Stein and their partner Bob Sassner, then Bob Axelrod in September 1946. In 1956 it became the sophisticated Culver House.

By early 1941, the glamorous Coral Isle was serving Chinese food, and, of course, tropical rum cocktails. 3/28/1941. Venice Evening Vanguard.

The Bambu Hut

Harold La Van had operated a club at 25 Windward Avenue in Venice since the mid 1930s. On February 2, 1940 he reopened it as the Bambu Hut with a new, tropical theme. La Van soon moved on to other ventures, including the Coral Isle, but the Bamboo Hut continued under various managers into the 1950s.

Writing of the tropical saloon craze in his syndicated column of July 1940, Lucius Beebe noted that while most nightclub trends started in New York and spread West, “the rash of Beachcombers, Tropics, Bars, Hurricanes, South Seas Saloons, and Zombie Palaces which is currently sweeping the land probably had its origin in Los Angeles, where Beachcomber Don has for years held forth in a gloomy grotto of strong waters, specializing in rum toddies of paralyzing dimensions… Just now there is hardly a self-respecting community in North America that hasn’t some sort of a beachcomber boozerie….”

Other crazes would come and go but Hollywood never really lost its fondness for things tropical. On December 7, 1941, all eyes turned to Honolulu, in horror, with the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. Following the US entry into World War II, Los Angeles became a port of embarkation for service personnel heading to the Pacific Theater. The China Clippers were painted olive drab, the Matson “Big White Ships” became grey and these romantic modes of transportation were drafted into military service. Waikiki Beach was closed off with barbed wire and The Royal Hawaiian became an R&R facility for the military. E.R. Gantt (Don the Beachcomber) joined the military and would go on to earn a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for his service.

On January 18, 1942, Hawaiian and Tahitian performers from 12 nightclubs, including Bob Brooks’ 7 Seas, Zamboanga, the Hula Hut and Gene’s Hawaiian Village, lent their talent at a rally for defense savings stamps and bonds at the Defense House in Pershing Square and drew the largest crowd to date.

Tropical-themed bars and restaurants became more popular than ever during and after the war and, of course, Don the Beachcomber’s, the Seven Seas, The Cocoanut Grove and King’s Tropical Inn remained fixtures for decades.

Notes

Bios of Gantt typically state that he changed his name to Donn Beach in the 1930s after the success of don the Beachcomber. However, on official documents of the 1940s and 50s such as his WWII draft registration and ship passenger lists, he was still using his birth name.

1722 McCadden became another tropical-themed club in 1937 after Don moved out, The Tahiti.

Tom Breneman died of a sudden heart attack in April 1948, leaving behind a wife, two young children, and thousands of devastated fans. Breneman’s restaurant continued to operate for a time, following his passing, but the contents were finally sold at auction in January 1950. The space became the new home of ABC radio.

This was not the first cafe in Los Angeles to be called the Hawaiian Hut. Ex-boxer/dentist Leach Cross had opened a Hawaiian Hut at 12745 Ventura Boulevard, across from the Hollywood Country Club, on December 10, 1925, but quickly tired of the venture and sold it in 1927 and his Hawaiian Hut became The Romany Shack.

Mayor Shaw was ousted in a recall election in September 1938. Hoy would be among the officers purged from the LAPD in March 1939 by Shaw’s replacement, former Superior Judge Fletcher Bowron, who campaigned on a reform platform.

The Masque Theater opened in 1926 as a legitimate state theater. In 1950 it was converted into a movie theater and renamed The Vagabond, probably because of Chastek’s popular restaurant, which became the La Fonda in 1969.

The high turnover of 335 N. La Brea smacks of mob.

There was also a postwar club called the Bambu Hut, located in Ontario at 522 W. A Street.